Intro

Mindfulness is the practice of living each moment with awareness, kindness, curiosity, and acceptance. A mindfulness practice can help you center your mind, relax your body, generate peace and joy, soothe painful emotions, develop emotional intelligence, and cultivate inner freedom. Mindfulness isn’t always easy to practice, and even people who have been practicing in a monastery for several years still get distracted sometimes 🙄 but if you train diligently, you will be able to produce these benefits more or less on demand, and you will notice a positive difference in your mental health.

My name is Brother Promise. As a teenager, I suffered from psychosis, and it was no fun. When I was 18, I attended a mindfulness retreat at Plum Village, a monastery in the south of France founded by Zen master and peace activist Thich Nhat Hanh, the person most credited with introducing mindfulness to the West.

One thing I loved about mindfulness was that it was empowering — here was a simple practice I could use anytime, anywhere, to take care of my mental health. One year later, at age 19, I returned to Plum Village to request monastic ordination.

In this article, I will give you a complete introduction to mindfulness: what it is, how to practice it, and some of the science behind it. So without further ado, let us “mindfully” jump into it.

Mindfulness

Most of the time, we think too much. We function in what neuroscientists call the Default Mode Network. In this mode, we ruminate on the past, we worry about the future, we judge ourselves, or we worry about how others perceive us. Evolution has hardwired us with these mechanisms to increase our chances of survival, but what helps us survive is not necessarily what makes us happy. In an important research paper called “A Wandering Mind Is an Unhappy Mind”, published in the journal Science, the authors conclude,

To become happier, we want to redirect our attention to the present moment. We want to reconcile our mind with the here and now, and engage with life as it is. This is mindfulness, and this is a trainable skill. The more mindful we go about our life, the more clarity we have to appreciate conditions of happiness and deal wisely with difficulties.

The practice of mindfulness originated with the Buddha, a spiritual teacher in the 6th century BC in India.

Mindfulness then spread to other Asian countries, and has recently entered global, mainstream, secular society.

In Pāli, the language of the Buddha, the word for mindfulness is “सति”, “sati”,

and sati also means “remembering”. Mindfulness is the practice of calling our mind back to the present moment, whenever we remember.

Translated in classical Chinese, sati became “念”, “niàn”.

The upper part of the character means “present moment”, and the lower part means “heart” or “mind”, because mindfulness is the practice of keeping our heart and mind in the present moment.

Translating “念” into Emoji is not a task to be taken lightly but I believe we have an excellent candidate in the TURTLE emoji

because the turtle is at home in her body, at home in the present moment, wherever she goes. And this is the power of mindfulness.

[⚠️ This article may contain weird, nerdy, deadpan humor. Please read at your own risk.]

But enough scholarly digression for now.

Just remember that to be mindful is to keep your mind in the present moment.

When practicing mindfulness, we don’t fight our disturbing thoughts, but we invite them to connect with what’s happening in the here and the now. There are many objects in the present moment we could chose to direct our attention to. But there is one object which the Buddha favored, and this object is… the breath. The Buddha even said, “If there is one meditation which can be rightly called the meditation of a Buddha, it is mindfulness of breathing.”

Mindfulness of Breathing

The breath is the mindfulness object which works best for most people most of the time. For this reason, mindfulness of breathing is at the heart of most mindfulness practices. Anchoring your attention on your natural in- and out-breaths can regulate your nervous system and help your mind grow calmer and clearer.

Not only the Buddha, but many other people throughout history have noticed that the state of our breath is tightly linked to our state of mind.

The ancient Greek word phren

referred to both the diaphragm and the mind. It is from “phren” that we obtained the English words “phrenitis” (an inflammation of the diaphragm) and “frenzy”.

The Latin word

referred to both the breath and the mind. From spiritus came the English words “respiration” and “spirit”.

Furthermore, the exhaling face emoji

reveals both a forceful breathing pattern and a distressed state of mind, and again demonstrates the close connection between breathing and mental health.

But enough scholarly digression for now.

Just remember that befriending your breath can benefit your mental health.

Your respiratory rate is your average number of in- and out-breaths per minute. It is a significant marker of neurological health, and I’d like to invite you to measure yours right now. Please sit down, or lie down, and let your breath be natural. You will soon be counting your natural breaths… starting now. Breathe in naturally, and on the natural out-breath count 1, breathe in naturally, and on the natural out-breath count 2… at your own rhythm. You’re not controlling the breath, you’re just counting how many natural breaths you take in one minute. And, stop. How many breaths did you take?

This infographic is simplistic but useful.

On the left is the first red zone, where you don’t want to be. Between 0 to 3 breaths per minute, you’re either dead or so relaxed you can hardly function. Between 3 to 9 breaths per minute is the green zone, where you want to be. You’re calm and centered, yet you’re also alive and responsive. Beyond 9 breaths per minute is another red zone because the more you breathe, the more stressed you become. Of course, during physical effort or when under stress, your breath will accelerate, but most of the day, you want your respiratory rate to be around 6 breaths per minute.

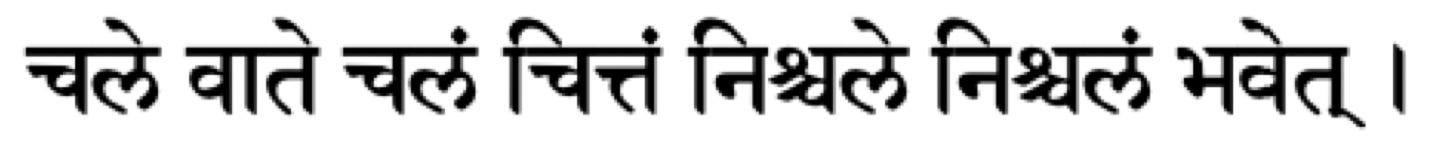

In the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, a sacred text of Yoga written in the 15th century CE, we read,

“When the breath is agitated, the mind is agitated, but when the breath becomes calm, the mind also becomes calm.”

According to modern science, faster breathing is associated with increased activity of the sympathetic nervous system, which is our fight or flight mode, while slower breathing is associated with increased activity of the parasympathetic nervous system, which is our rest and restore mode. The way I like to put it is, a short breath is for short-term survival, and a long breath is for long-term happiness. As our breath slows down, our heart rate slows down, our blood pressure goes down, and our internal organs such as our brain receive more oxygen. We relax, we feel better, and we think more clearly.

When practicing mindfulness, we never control the breath. We simply tune in and pay attention to our natural breath, with presence and patience, and allow our breath to slow down by itself.

Let us try mindful breathing together.

Your back is straight and relaxed.

Your mouth is closed. You only have one breathing organ and it is your nose. Your nose filters, warms, and moistens the air. It also maintains a slower, more regular air flow which is conducive to relaxation and deeper oxygenation. So please try to only breathe through your nose.

Your eyes can be open or close, whichever feels most comfortable, but if your eyes are open, please keep them relaxed and only look in front of you.

Now, keeping your attention light and open, gently tune in the sensations of your breath naturally coming in and naturally going out. On the in-breath, notice the cold air entering your nostrils, and your lungs, ribcage and belly expanding, and on the out-breath, notice your belly, ribcage, and lungs collapsing, and warm air leaving your nostrils. Make sure you are not controlling the breath. When you notice your mind contracting on and controlling the breath, loosen it up. And when you notice your mind logging out of the breath, gently bring it back. You want to be in the sweet spot where you are aware of the breath as it is, without controlling it. Keep your mind light and open and stay with the breath, for as many breaths in a row as possible. Of course, you will get distracted. Everyone’s mind is like this, and this is part of the game so please be kind to yourself. When you notice you got distracted, simply tune back into the feelings of your natural breath. Your attention is surfing the breath. Try not to fall. But when you do, smile, get back on the breath, and again, try to “stand on” the breath for as many breaths in a row as you can. Your mouth is still closed. You are not thinking about your breath. You are feeling your breath, naturally coming in, and naturally going out. Whenever you get distracted, kindly and patiently bring your mind back to your breath. In mindfulness, although there is focus, there is no straining. It’s a light type of focus. If you can distinguish whether you’re breathing in or out, your mindfulness is good enough. Your task, then, is to make your mindfulness enjoyable and keep it going. You are present to the breath just as it is. You are patient with the breath, aiming for a continuity of mindfulness, breath after breath after breath, enjoying as many breaths in a row as possible.

If you practice this for a few minutes, you may notice your breath becoming longer, deeper, quieter, and more regular. With the slowing down of your breath, it becomes easier for your body to relax and for your mind to quiet down. Relaxation is not something you can force. Relaxation happens naturally as you pay attention to your breath, without control or contraction.

While keeping your mind anchored on your breath, also notice the other things happening right now, such as your other physical sensations, the sounds and sights unfolding around you. The Buddha taught, “right concentration is neither outwardly scattered nor inwardly restrained.” When practicing mindfulness, you neither want to be carried away by what’s outside nor stuck with what’s inside. Mindfulness doesn’t ask you to imprison your mind in your breath but to make your mind at home in your breath, and open up your windows to the present moment. Stay aware of your breath coming in and going out naturally, as you notice what is happening around you, with an open heart, not discriminating too much between likes and dislikes. Allow all sensations and sensory inputs to flow the way they want to flow. Keep paying gentle attention to the present moment, aware of your breath, and open to everything else.

Article republished with permission from mentalhealthrevolution.org