This is the final part of our Mindfulness series. In it, we continue our discussion of Emotions and dive into the Four Establishment of Mindfulness and offer some closing reflections. If you have enjoyed this series and would like to deepen your understanding of Mental Health, feel free to join the Mental Health Revolution.

An Emotion is an Interaction

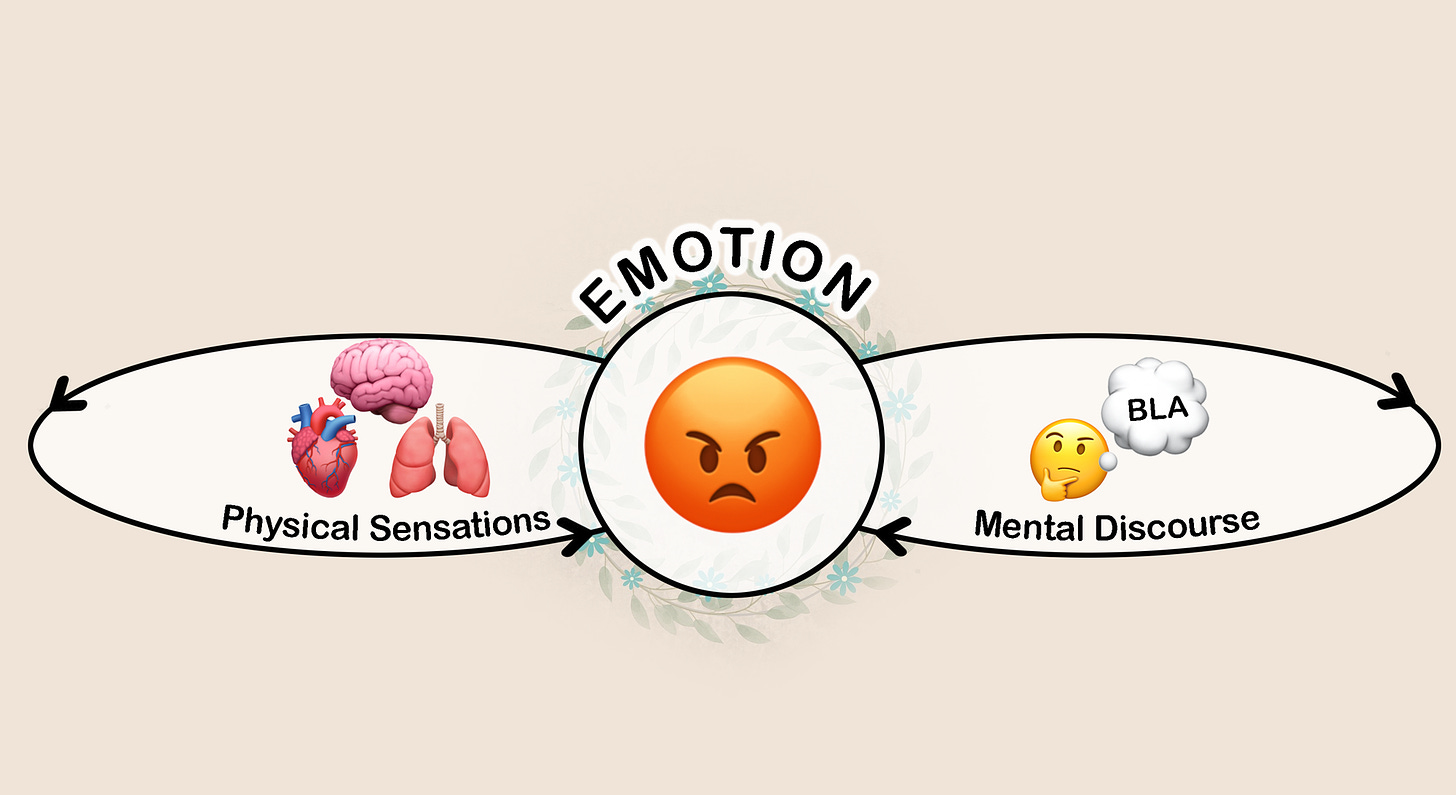

An emotion is an interaction between physiological processes and a mental discourse. For example, when we get angry,

at the physiological level, our heart accelerates, our muscles tense up, our blood pressure goes up, and we get hot, while at the mental level, we may think, “I can’t believe he did that! This is so unfair!” Or when we are sad, we may get cold and feel sluggish in our body, while in our mind we may tell ourselves, “This is terrible. Why does this always happen to me?”

Our physiological processes and our mental discourse also influence each other. For example, when we are sleep deprived, our thoughts are more negative. Or when we think about a difficulty in our life, our stomach or shoulders may tense up.

But an emotion is always an interaction between physical sensations and a mental discourse. Therefore, to work with your emotions is to work with your physical sensations, or your mental discourse, or both.

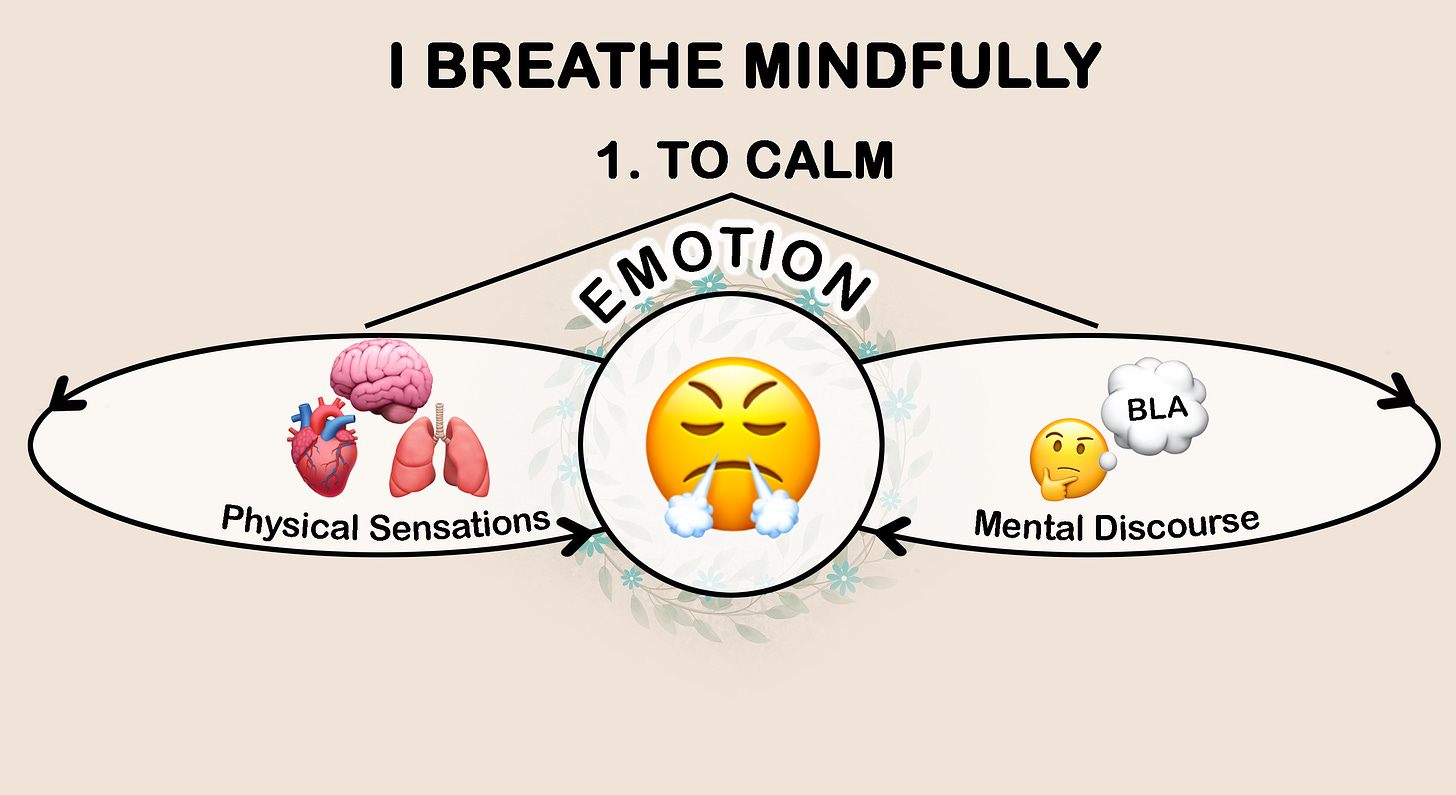

When you pay attention to your breath, you calm down both the mental discourse and the physical sensations.

If your thoughts were a fire, your attention would be its fuel. The more you pay attention to the content of your thoughts, the more they grow, and the more they burn your peace of mind. By shifting your attention away from your mental discourse and toward the sensations of your breath, you naturally deprive the fire of some of its fuel, and your mental discourse grows quieter.

At the physiological level, as we’ve seen, when you focus on your natural breathing, your breathing naturally becomes smoother and slower. With the slowing down of your respiratory rate, sympathetic nervous system activity decreases and parasympathetic nervous system increases. Your body begins to relax, your heart rate slows down, your blood pressure goes down, and your internal organs such as your brain receive more oxygen. You operate less in short-term survival mode, more in long-term happiness mode, and you pacify your entire physiology.

Our natural tendency is to try to solve our problem immediately by thinking. But if you remember the analogy of the musician, if our nervous system is out-of-tune, our thoughts won’t be of good quality. When our nervous system is agitated, the more we think, the more confused we become. Therefore, it is very important that we focus on our breath, regulate our nervous system, and calm our body and mind before we begin to think about the situation.

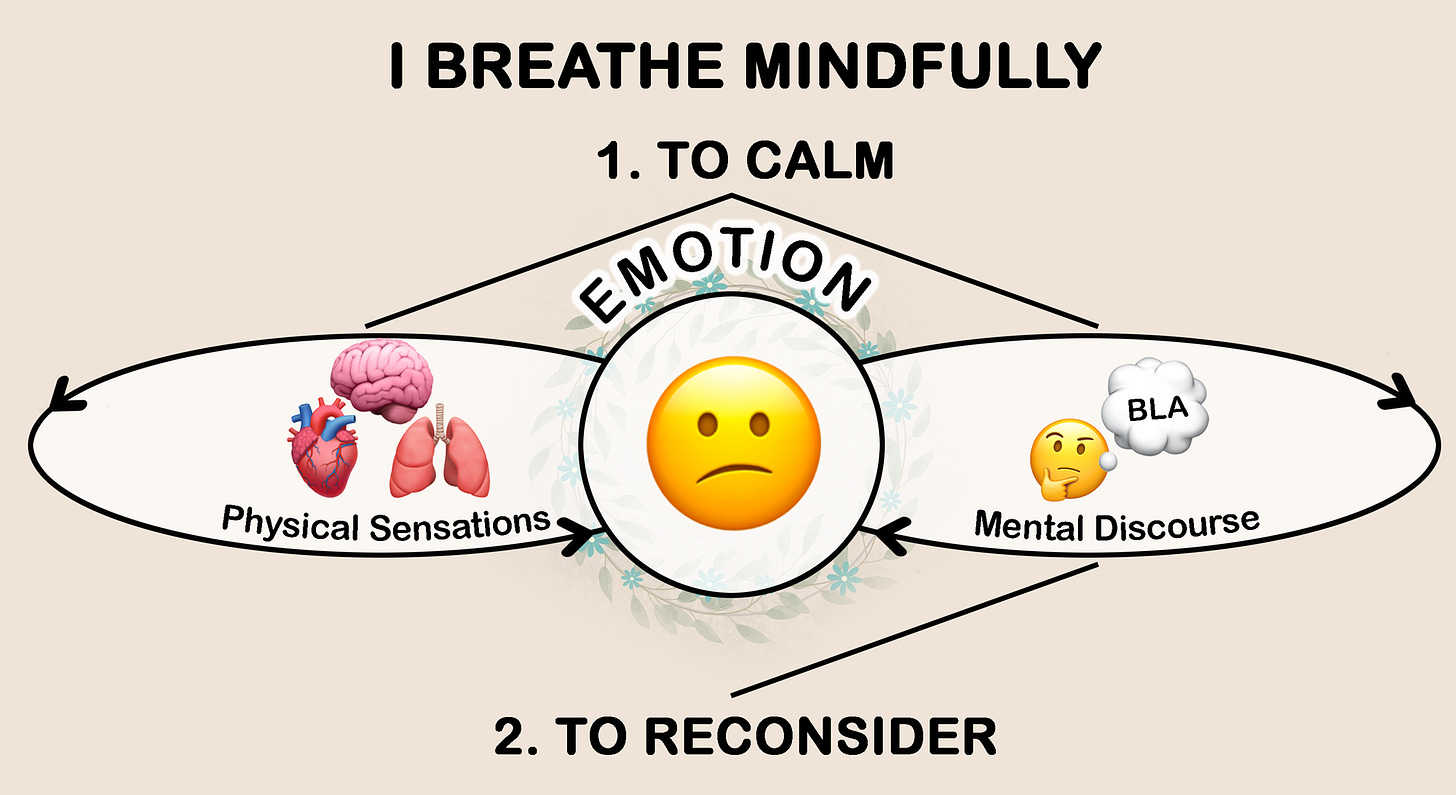

Once we are calm enough, we can gently reconsider the story we’ve been telling ourselves.

In psychology, this is called “cognitive reappraisal”. Cognitive reappraisal is simpler than it sounds. It simply means looking at our mental discourse, the story that our mind is telling, and asking ourselves, “Really?” Cognitive reappraisal is not autosuggestion — we’re not trying to convince ourselves of anything in particular. It is calm, curious, and critical thinking. We invite our mental discourse to a reality check. We reconsider the content of our thoughts in order to look at the situation in a way which is more accurate, actionable, and useful.

You can ask yourself,

- “Is this thought true?”

- “Is this belief helpful?”

- “How have I been contributing to the issue?”

- “How can I contribute better?”

When your mental discourse revolves around another person, you can also find the right time to check with them:

- “Did you actually say that?”

- “Did you actually do that?”

- “Why?”

- “What difficulty made you speak or act this way?”

At the risk of being redundant, for this reality check to be healing and effective, it needs to happen in your spacious and loving awareness, and that is why before you reappraise the content of your thoughts, you want to calm your body and mind by focusing on your breath, noticing your sensations and thoughts, cognitively defusing from the emotion, and reestablishing your connection with the fullness and spaciousness of the present moment.

We tend to misconceive problems as

- personal — “this is just about me”,

- permanent — “this will last forever”, and,

- pervasive — “this will inevitably lead to this terrible cascade of consequences and ruin everything in the universe”.

From your spacious and kind awareness, you may also want to ask yourself,

- Is this really just about me?

- Is this really going to last forever?

- Is it reasonable to extrapolate to this extent?*

Learn to see everything in the light of multifactorial change. Everything changes according to countless conditions. Nothing is personal, permanent, nor pervasive. People, events, and things are not the separate and stable entities your thoughts would have you believe. Everything is flowing. Whether you want it or not, everything is changing, in a state of flux.

When you follow your breath, you tone down the mental discourse, you get into a flow state, and you reduce friction with reality. With less friction between your consciousness and reality comes less suffering. Before, when you were totally absorbed in your mental discourse, it seemed like you were carving your life’s drama on a rock. But as you follow your breath, allow your body to relax, become more awake and equanimous, and notice how everything is changing, your mental discourse loses its grip. Now, it seems as if you are writing your life’s drama on sand… or even on water… or even on thin air. You are more aware, yet you take your life less personally. You are more conscious, yet you worry less, because you see things more as they are, flowing naturally according to conditions. This insight into multifactorial change can be very healing and liberating, even if you are only able to maintain it for a short moment. The Buddha encourages us to nurture it regularly. The more we can see how things change according to many conditions, the more accurate our understanding becomes, and the more space, lightness, peace, and freedom we bring to our mind.

The Four Establishments of Mindfulness

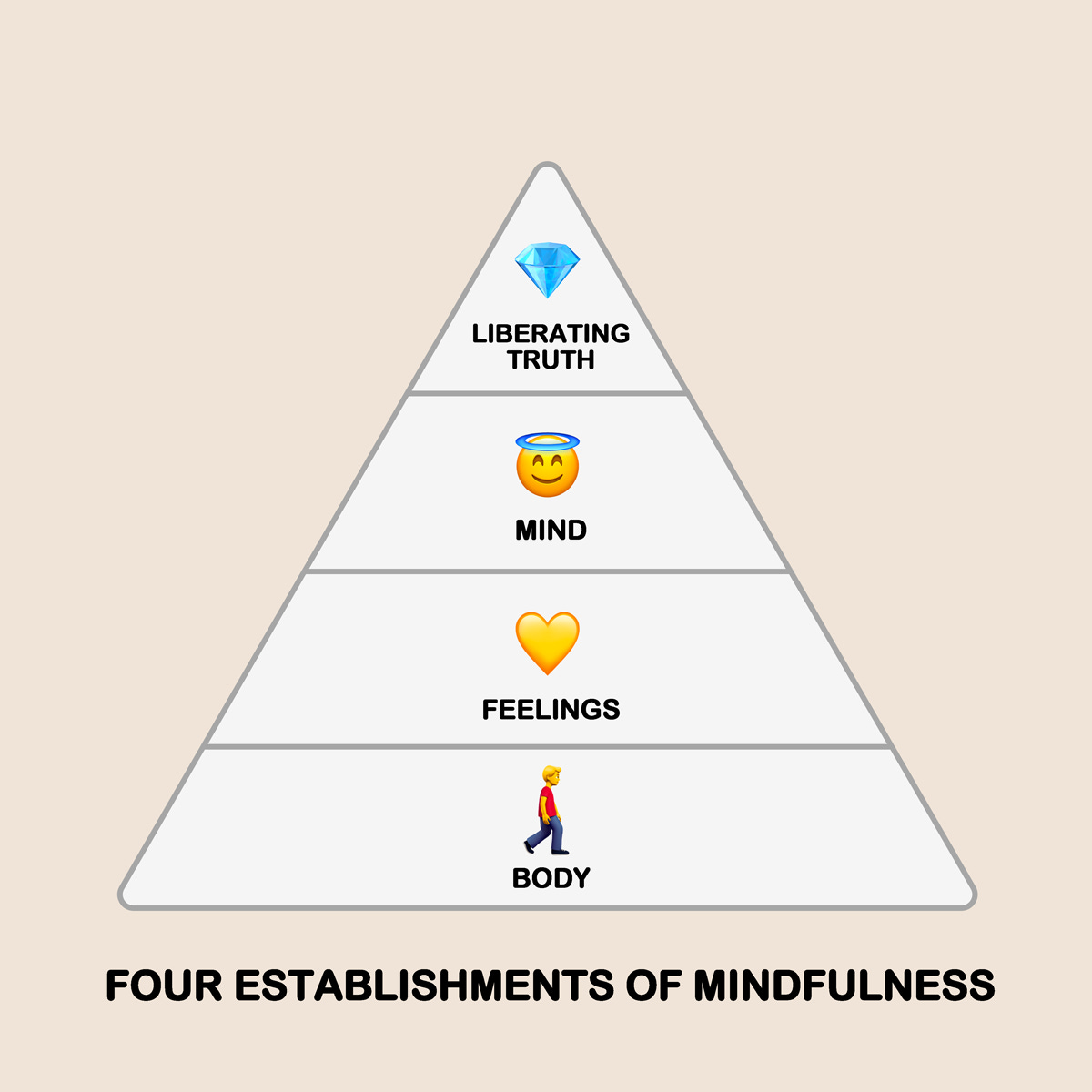

The Buddha taught four establishments of mindfulness: body, feelings, mind, and liberating truth.

Notice how he ordered them from the coarsest to the subtlest: body first, then feelings, then mind, then liberating truth.

The Buddha encourages us to establish our mindfulness in all of these four establishments — to become aware of our body as it is, in the present moment, without desire or aversion; to become aware of our feelings as they are, in the present moment, without desire or aversion; to become aware of our mind, as it is, in the present moment, without desire and aversion; and to become aware of the liberating truth, as it is, in the present moment, without desire and aversion.

- Mindfulness of our breath and body helps us come back to life, stay grounded, and physically relax.

- Mindfulness of our feelings connects us to our own humanity and softens our heart for others.

- Mindfulness of our mind helps us update our belief system and connect to life more as it truly is.

- And mindfulness of the liberating truth works with the deepest roots of suffering within our mind in order to cultivate spaciousness, lightness, and freedom. If you would like to learn more about the Liberating Truth, I have a book that you can download for free at mentalhealthrevolution.org/books/vipassana, as well as a series of videos on this channel called Experiments in Transcendence.

How Mindfulness Grows Our Emotional Intelligence

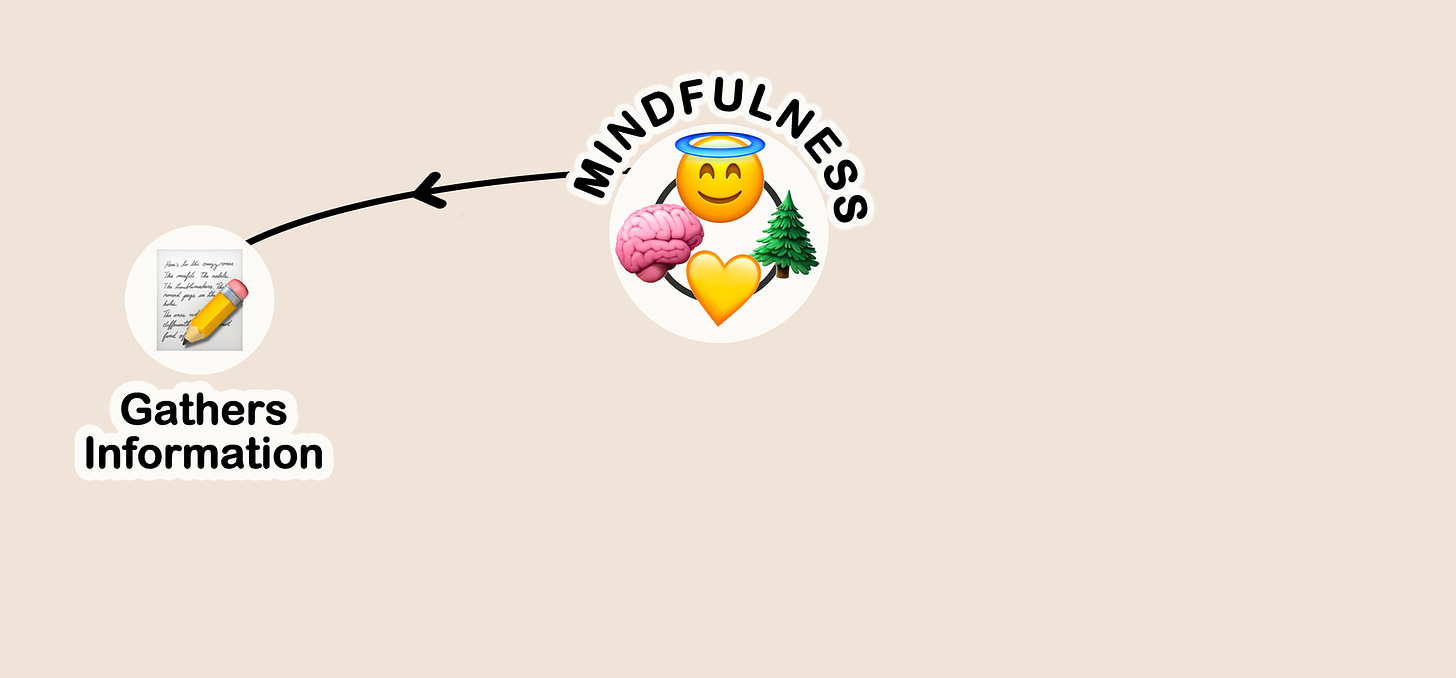

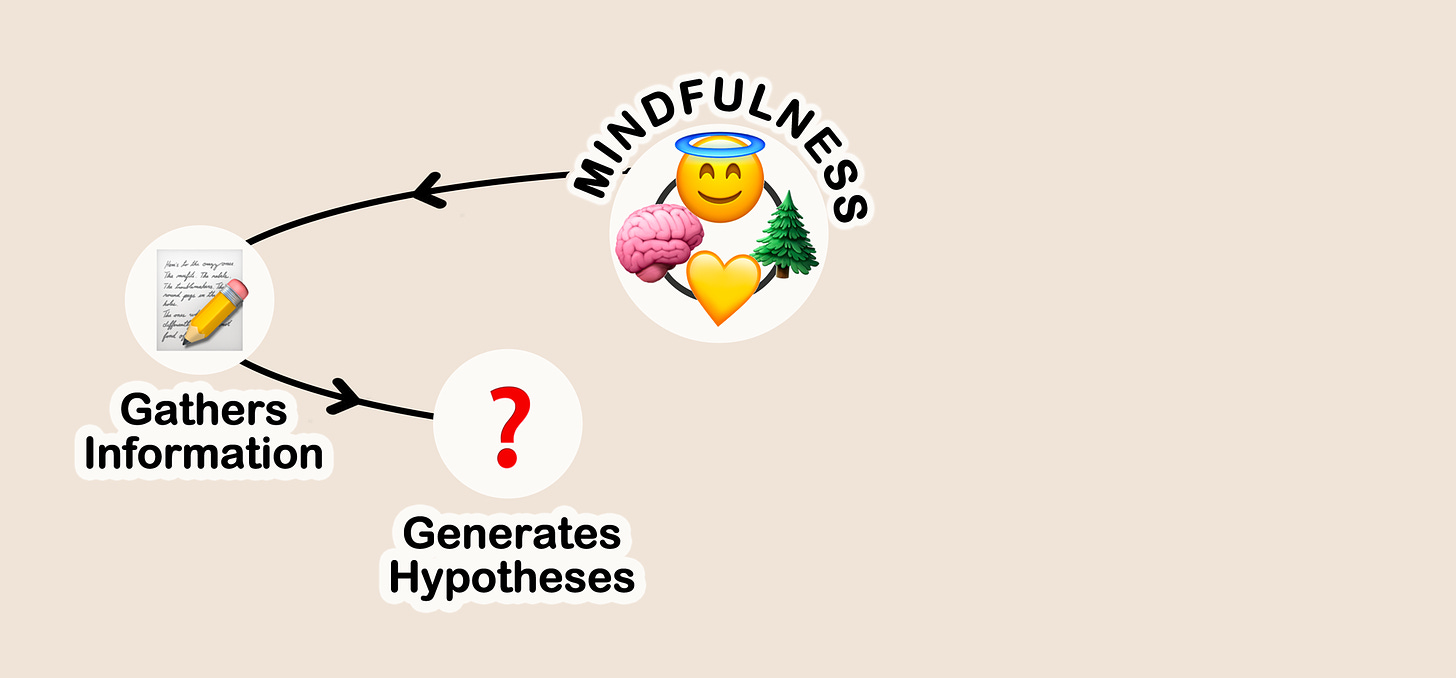

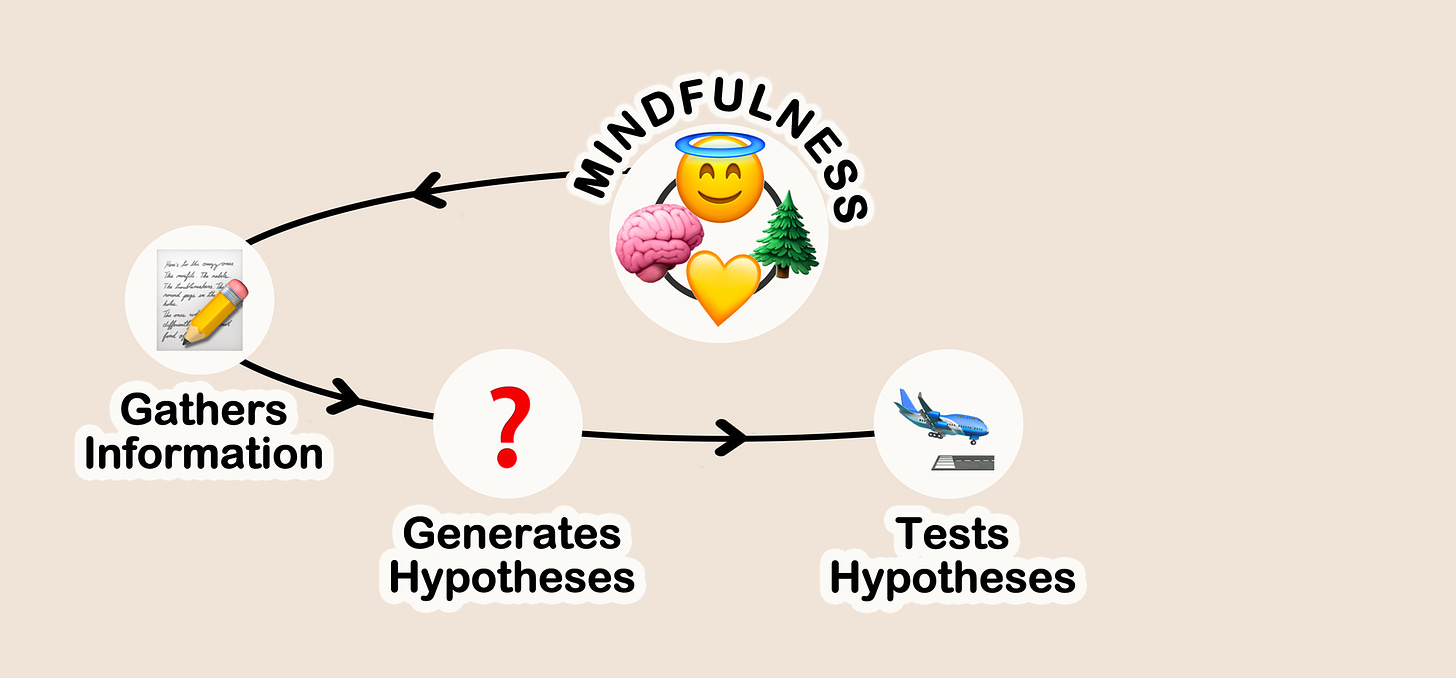

One way to explain how a mindfulness practice helps us develop our emotional intelligence is that the more aware we are of ourselves and our environment,

the more information our brain can gather about:

- what we think, say, or do,

- the types of environments and people we interact with, and,

- how we feel.

Overtime, our brain naturally generates new hypotheses

about how what we think, say, or do, or different environments and people, affect how we feel. For instance, “It seems like every time I think kind thoughts, I feel peaceful and happy.” “It seems like every time I criticize someone behind their back, I feel disconnected.” “It seems like every time I eat fried food, my stomach hurts.” “It seems like every time I go out into nature, I feel refreshed.”

Then, the next time we find ourselves in a similar situation, our brain naturally tests these hypotheses:

“Let me see if it’s going to be different this time, or if my hypothesis was correct.”

And slowly, we can learn from our own experiences,

update our belief system, develop our emotional intelligence, and naturally make decisions that are a bit more conducive to our own and other people’s long-term happiness.

Conclusion

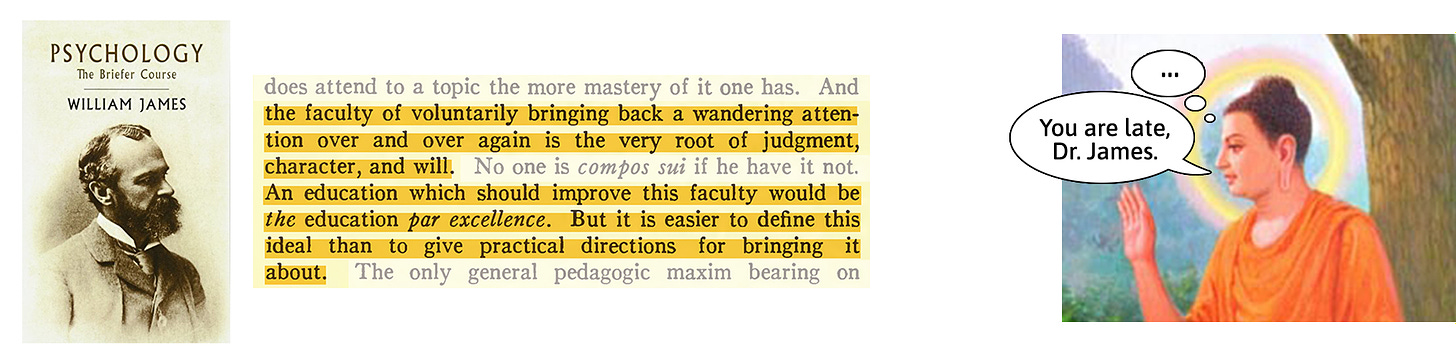

In 1892, William James wrote in his book Psychology: The Briefer Course,

The faculty of voluntarily bringing back a wandering attention, over and over again, is the very root of judgment, character, and will. […] An education which should improve this faculty would be the education par excellence. But it is easier to define this ideal than to give practical instructions for bringing it about.

Little did he know that 24 centuries before him, in India, an enlightened man did provide this education per excellence, did offer detailed, practical instructions in attention training, and that thanks to the countless people who have transmitted his teachings, we still have access to them today.

By cultivating mindfulness, an accepting awareness of the present moment, we decrease activity in our Default Mode Network and increase activity in our Positive Task Network — we think less compulsively and we become more conscious. Our respiratory rate slows down, we decrease sympathetic nervous system activity and increase parasympathetic nervous system activity — we stress less, and we relax more. We are able to appreciate our conditions of happiness more deeply, regulate our emotions better, and respond to challenges more wisely. If a wandering mind is an unhappy mind, a mindful mind is, indeed, a happy mind, and it is no wonder that mindfulness has been shown to be helpful in a wide range of mental health conditions.

In 2021, the journal Nature published an article entitled,

. The authors looked at 419 randomized controlled trials from clinical and non-clinical populations, totalling over 50,000 participants, and concluded that

Mindfulness can help,

- alleviate anxiety and depression,

- reduce stress, substance misuse, and risks of suicide,

- increase focus and foster creativity,

- promote prosocial behavior,

- sleep better, and,

- slow cognitive aging.

To be clear, I don’t believe there is such a thing as a cure-all for mental health, but I do believe that mindfulness should play a key role in any good mental health plan.

If you haven’t printed it yet, you can find your Daily Wellness Empowerment Program Sheet in the description box below. If you are a mental health professional watching this, please try the Daily Wellness Empowerment Program, because you also need to take care of yourself. And after you’ve experienced its benefits, you can print out lots of DWEP Sheets and leave them in your office, at your patients’ disposal.

Article republished with permission from mentalhealthrevolution.org