Grégoire Mauraisin (Bodhicita Awakening of the Source) is an aspiring writer living in Malmö, Sweden. He is an ambassador of the Wake Up Malmö Sangha and an active member of his local Buddhist temple in the Ch’an tradition. In his free time, Grégoire enjoys working out and walking mindfully in nature. In this article he shares with us his work on Thay’s calligraphies.

You can also learn more about Thay’s calligraphies by watching this short film on the Plum Village YouTube page.

Introduction

I have recently completed my Master’s degree in Literature, Culture and Media at Lund University in Sweden and, for the topic of my thesis, I choose to look at Thay’s literature. There are a few things I talked about but I wanted to share here some informations I have found on his calligraphy. In this article, I will discuss some historical background to Thay’s calligraphy and how this can help us appreciate his work.

Historical Background

Calligraphy, from the Greek words kalos (beautiful) and graphein (writing), can simply be understood as the art of writing beautifully. The practice of calligraphy has appeared throughout the world in countless different cultures. There are, however, several main branches of calligraphy that have been grouped together. The branch of calligraphy that Westerners would be most familiar with is known as Western calligraphy. It is the branch of calligraphy that uses primarily the Roman alphabet, though it can also include the Greek and Cyrillic one. As Thay does use the Roman alphabet for his calligraphy, it can be argued that his work belongs in this branch. However, the tools that he used are different from the traditional tools used by Westerners. Instead of the quills and pens that Western scribes were used to, he used the traditional set of brush, ink, rice paper and ink stone, also known in Chinese as the Four Treasures of the Study. It is these tools that gives East Asian calligraphy its unique aesthetic present in Thay’s work. In that sense, his calligraphy practice is well rooted in an ancient Asian tradition that is important to understand in order to have a deeper insight in his work.

East Asian Calligraphy is a broad term that encompasses different calligraphic styles whose primary alphabet are the East Asian Characters. It includes Chinese, Japanese, Korean and Vietnamese calligraphy. However, the oldest form of East Asian calligraphy known today is the Chinese calligraphy, all other East Asian calligraphy then derive from the Chinese one.

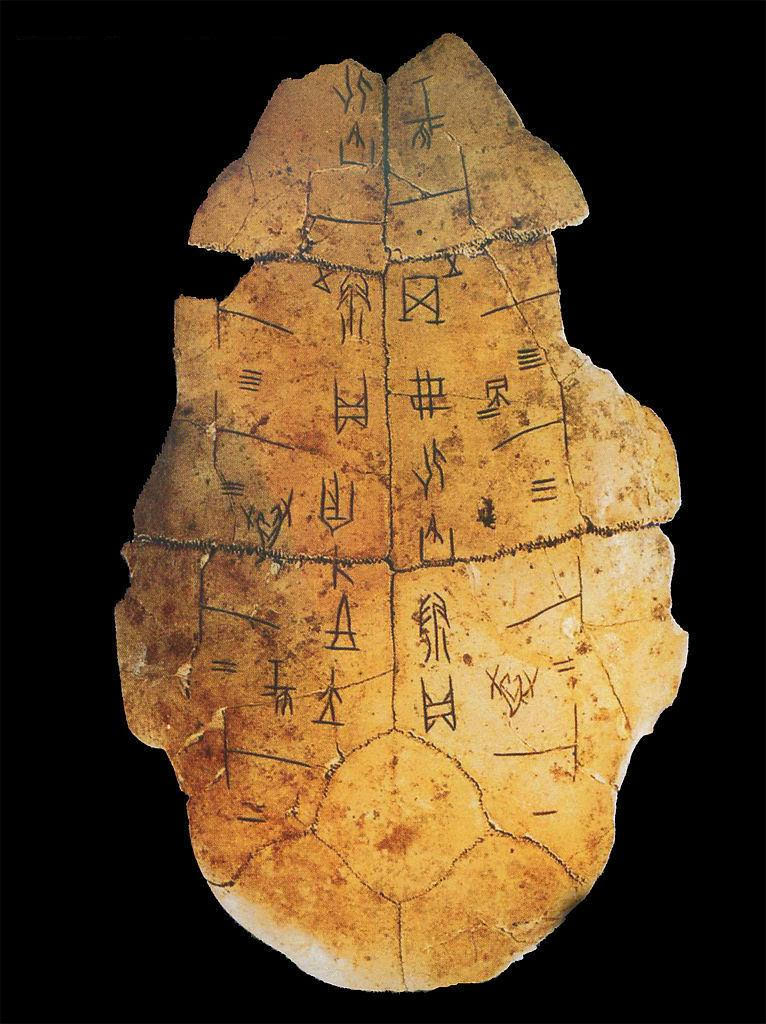

According to Stephen Little, Chinese Calligraphy can be traced back to the beginning of the Bronze Age, around 2000 BCE. The earliest known form of Chinese writing was found on oracle bones; rune like objects that were used for divination (373). The script present on the bones, simply called Oracle Bone Script is considered the direct ancestor of over a dozen East Asian writing system that develop over three millennia.

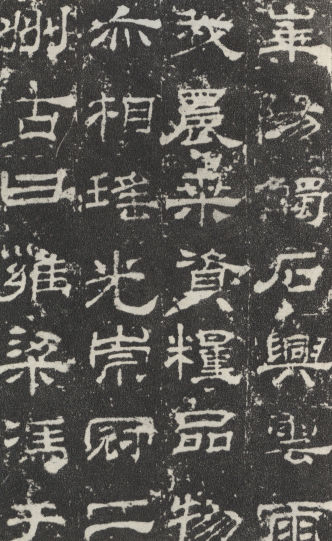

As inscription were made on rough surfaces, the Oracle Bone Script contained many straight and angular lines. Over a couple thousand years this script evolved into numerous new scripts. The script that is most noteworthy for understanding East Asian calligraphy is the Clerical script, which is thought to have appeared during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE- 220 CE). This script is of importance because it was the first one in which the physical movements of the writer’s hand could be seen through the strokes of ink (Little, 375). It was during this period that calligraphy began to be thought of as an art form. In fact, the Clerical Script is still sometime used by calligraphers today.

But, according to Lothar Ledderose, it was during the Six Dynasties (220 CE – 589 CE) that calligraphy was truly elevated to an art form that was practiced by the educated elite (246). It was then that calligraphic pieces were for the first time collected as works of art, that theoretical treatises on calligraphy began to be written and that three new scripts received their final formulation. It was also during this time that the Four Treasures of the Study were formalised.

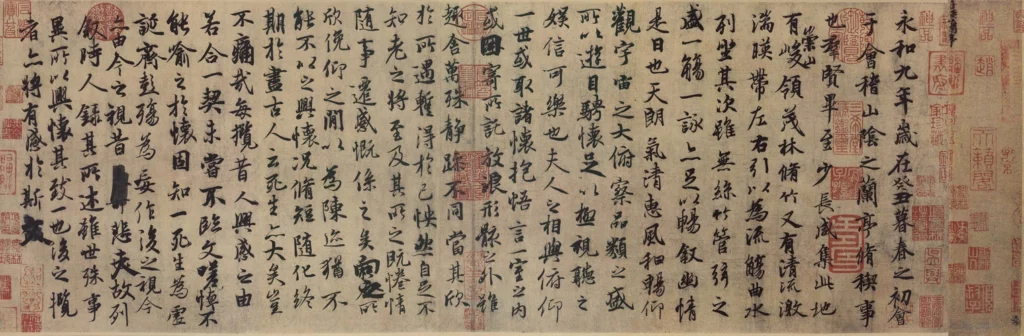

The formalisation of these tools led to the development the Cursive Script, the Semi-Cursive Script and the Regular Script. Since the officialisation of these scripts, no other script has seen the day. These scripts were most notably brought to “the apex of classical perfection” (Little 375) by Wang Xizhi (303-361) and his son Wang Xianzhi (344-388), the most celebrated calligraphers in Chinese history. Together they became known as the Two Wangs, and their style, especially Wang Xizhi’s, “served as the basis for a coherent stylistic tradition that dominated the history of Chinese calligraphy for more than a millenium” (Ledderose 246). The classical style led by the Two Wangs greatly shaped the practice of Calligraphy in Ancient China and greatly inspired neighbouring cultures, including Vietnam.

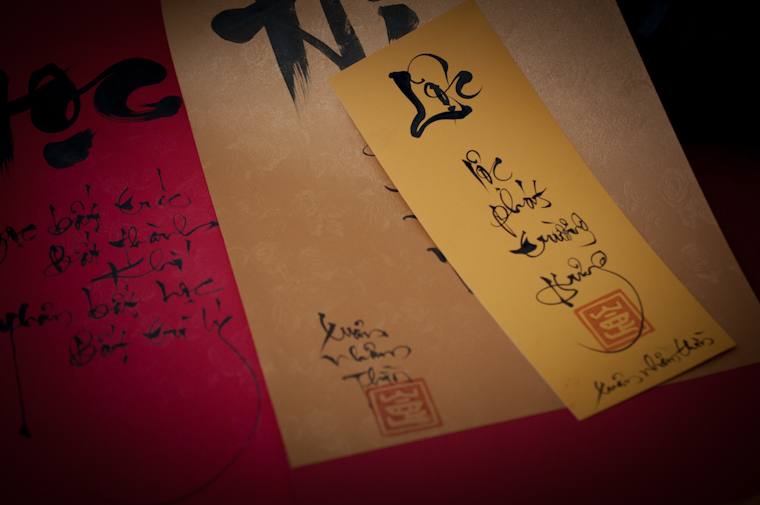

The work of Wang Xizhi and his son served as the basis for many East Asian practices. As China had a powerful influence on neighbouring countries, this style eventually became highly regarded by Vietnamese calligraphers too. Over time, Chinese and Vietnamese calligraphy grew to be different while retaining the traditional use of the Four Treasures. A notable change of Vietnamese calligraphy, unique to all other East Asian style, is the inclusion of the Roman alphabets. Following the colonisation of Vietnam, the French enforced, in 1910, the current Vietnamese alphabet known as chữ Quốc ngữ. This alphabet became mainstream by the 1920s and is now widely used in Vietnamese Calligraphy.

Thay was a direct descendant of this ancestral lineage. Brother Phap Huu, once explained that Thay started calligraphy as a hobby in 1994, first to illustrate books, songs and articles, and eventually to decorate Plum Village. Thay’s calligraphies display a unique mix of traditional East Asian component and English or French phrases. They are now an important part of the Plum Village tradition and have been exposed in museums and universities world-wide.

Appreciating Thay’s Calligraphy

As calligraphy played such an important role in Ancient China, many ways to appreciate calligraphy can be found there. In an article on that subject, Xiongbo Shi, researcher at Shenzhen University, argued that calligraphy appreciation involves bringing into awareness the brushwork and their spiritual qualities in calligraphic works (487).

This approach was first stated in the Six Principles of Chinese painting, written by Xie He (500-535). The two first principles that he used to define a good painting were “animation through spirit consonance” and “structural method of the brush” (487). Spirit consonance can be understood as the portrayal on paper of the artist mind state, and the structural method of the brush refers to the unique style of the artist, like the uniqueness of one’s own handwriting. This means that calligraphies were seen by Chinese critics as containing an outer from, its formal features, and an inner from, its spiritual dimension. However, of the two dimensions, Shi argues that it is “unanimous that the latter deserves more attention in judging calligraphy” (488). He quotes the eight-century critic Zhang Huaiguan as saying: “Those who know calligraphy profoundly observe only its spiritual brilliance and do not see forms of characters” (488). That is because the brushwork itself is informed by spirituality. For instance, Ledderose noted that a defining feature of Wang Xianzhi’s work was the element of Tzu-Jan, which he translates as “spontaneity,” one closely linked to the Taoist philosophy and the notion of “a free, unobstructed flow” (266). In other words, Ledderose found the brushstroke of Wang Xianzhi, to be a direct manifestation of Taoism.

Understanding the brushstrokes as spiritually significant is a great way of gaining insight into Thay’s work. But before visually understanding the brushstrokes, there are a few important things to note that are not evident to the eye. First, Thay was famous for mixing a little bit of his tea with his ink before doing calligraphy. This tea served as a token of Interbeing, arguable one of his most famous insight. The second thing is also connected to the idea of Interbeing. In the West, we have many ideas rooted in dualism and that is also true for the artist/art relationship. But, according to Thay’s teachings, these dualistic ideas are only products of our mind. Rather than seeing the artist and the art as two separate entities, he would note that they inter-are. The artist cannot be an artist without his art and the art cannot be without an artist. But the artist also inter-is with everything else. For that reason, Thay noted that:

The hand that draws the calligraphy does not act alone. It is connected to my whole body, my mind, and all the cells in my body. I like to invite all my cells to join me in making a circle. These cells don’t exist by themselves either. I invite all my ancestors to draw the circle with me, as well as all the people whose lives have touched mine. My whole community is in each calligraphy. Please don’t think that these calligraphies are drawn by one person alone. We as a community have drawn this circle together. (10)

This shows how the insight of Interbeing is at the heart of Thay’s practice and allows to further understand his work. Thay once argued that seeing that we are not separate from each other allows for the arising of compassion. Then, this compassion is manifested in being truly present, caring, loving and gentle with all things. It is exactly those qualities of care, love and gentleness that are visually found in his work.

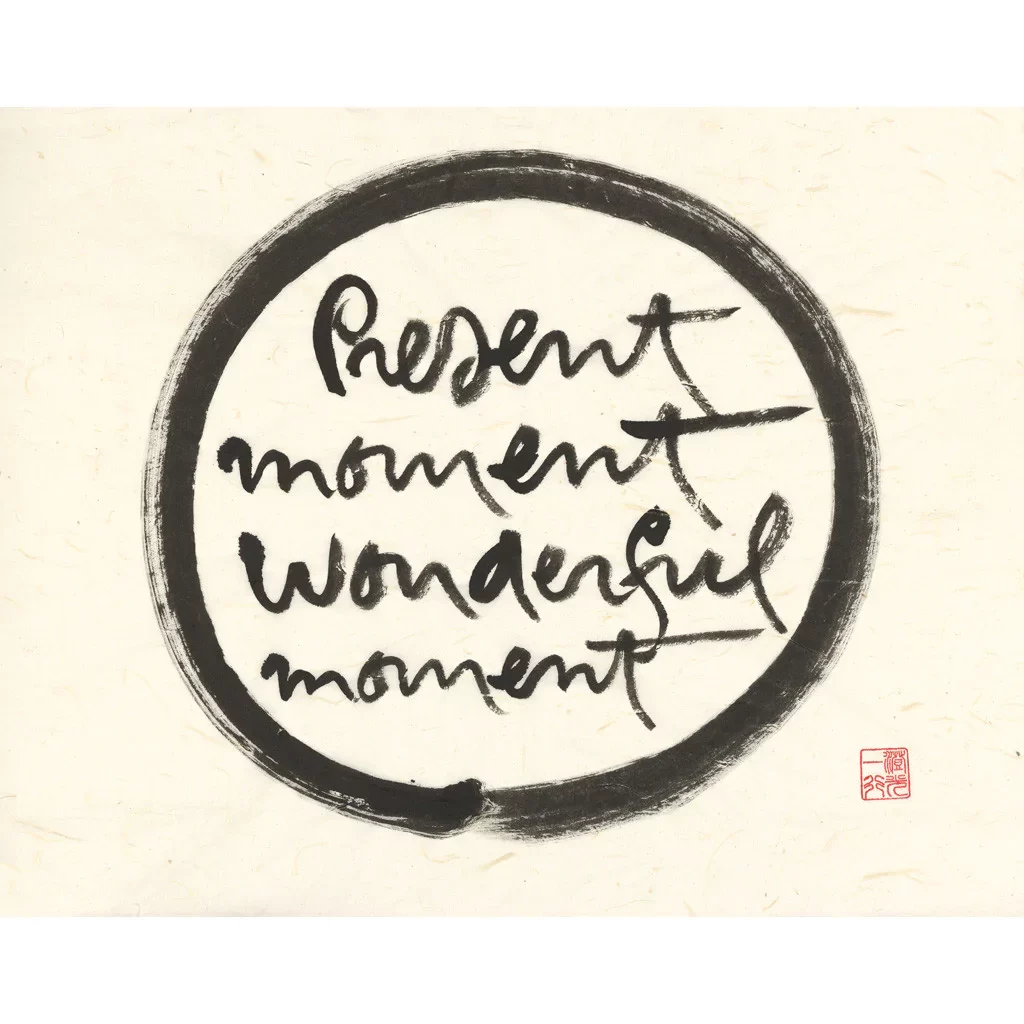

To illustrate this, let’s look at the first line of “Present moment Wonderful moment.” By taking our time visually retracing his work, we can see the care and gentleness that went into creating the P with a single brushstroke. Thay appears to have first put his brush on the bottom part of the letter and then slowly moved upwards and delicately twisting his brush to create the curve of the P. Then, with a single and continues brushstroke, we wrote the “res,” which displays the same peaceful qualities. The “ent” also appears to be a singular brushstroke, except for the T-bar being an independent stroke. Altogether the brushstrokes seem to constitute an embodiment of Thay’s philosophy. Each of them are deeply informed by the insight of Interbeing and display the care and gentleness that this insight offers.

There is another thing to note, the presence of the Zen circle. This circle is known as the Enso, and is a proeminent feature of Japanese Zen calligraphy. The Enso is also somewhat linked to the insight of Interbeing. In her book, Enso: Zen Circles of Enlightnement, Audrey Yoshiko Seyo explains the circle to be a symbol that “encompasses and conveys a continuing and ceaseless action through all time” (xii). But she also notes that there is no definite and fixed-upon meaning of what the Enso symbolizes. Another idea is that it represents Emptiness “the fundamental state in which all distinctions are removed,” a state where all dualistic notions are abandoned. Traditionally, the Enso was also seen as “a direct expression of thusness or this-moment-as-it-is” and Seyo argues that in Zen it is considered to be one of the most profound subjects, one that exposes the most directly the mind state in which the circle was produced (xii). Looking at “Present moment Wonderful moment,” one can notice, the precise uniformity of the circle and the gentle and free continuation of the brushstroke. There appears to be no pause, but rather a single, smooth brushstroke with a clear beginning and end. In that sense, the “spiritual brilliance” of the circle seem to align well with the gentleness reflected in the brushstrokes present in the text.

The final noteworthy element, one proper to East Asian calligraphy, is the presence of a red seal. The seal, often known as “hanko” in Japanese, act as Thay’s signature. However, I have found no sources that discusses the meaning of the symbol present on his hanko, neither from Thay nor from academics. A thing to notice, however, is that Thay’s hanko is easily recognizable by its singular single line in the top left corner and the house-shaped sign underneath it. These features appear on all of Thay’s published calligraphy and the calligraphy created by Brother Phap Huu display a different seal.

In conclusion, Thay’s work is a direct continuation of a long tradition that finds its root in 2000 BCE China. With the millennia, the practice has drastically transformed to become what it is today. The most notable feature of Thay’s style is the use of the Four Treasures of the Study and the inclusion of the Roman alphabet. Chinese Calligraphers also provided ways to look deeply into calligraphy. When one looks at Thay’s work from this angle, one can see that each of his brushstroke is an embodiment of the care and gentleness generated by the insight of Interbeing.

Works Cited:

Ledderose, Lothar. “Some Taoist Elements in the Calligraphy of the Six Dynasties.” T’oung Pao, Vol. 70, 1984, pp. 246-278. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/4528317.

Little, Stephen. “Chinese Calligraphy.” The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art, Vol. 74, no. 9, 1987, pp.372-403. JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/25160005.

Seyo, Audrey Yoshiko. Enso: Zen Circles of Enlightnement. Foreword by John Daido Loori, Shambhala Publications, 2007.

Shi, Xiongbo. “As if one witnessed the creation: rethinking the aesthetic appreciation of Chinese Calligraphy.” Philosophy East & West, Vol. 70, no. 2, Apr. 2020, pp. 485-505. University of Hawai’i Press, doi: 10.1353/pew.2020.0031.

Hanh, Thich Nhat. The Way out Is in: The Zen Calligraphy of Thich Nhat Hanh. Thames and Hudson, 2015.

What an excellent study!! Very deep and insightful ❤️ thank you so much for sharing this. I love the concept of interbeing by Thay! ✨ A lotus for you,

Thank you kindly for the effort and scholarship you put into writing this piece on Thich Nhat Hahn’s calligraphy. It certainly is beautiful writing and inspiring to view.

I would note in addition to your insightful comments on the hanko stamps in Thay’s calligraphy, that Nhat Hahn translates to One Action. This name corresponds to left upper and lower pictographs in the hanko, the horizontal line reading One and the below house-shaped sign reading Action. These are often written in an ancient seal script and are challenging to read. I have been using Kazuaki Tanahashi’s book The Heart of the Brush to better understand seal script.

Thanks again.