Monastic Sister Hien Nhan is now twenty-six years old and lives with the sisters in Lower Hamlet. She grew up living across many different countries and celebrating her French, Canadian, and Mexican heritage. In this interview, Sr. Hien Nhan speaks about her path to monastic practice and the various manifestations of her quests for truth. She also discusses the grounding and support she has felt at Plum Village, and the beautiful offerings of Vietnamese culture she experiences on a daily basis. This interview was conducted by Annica Bauer shortly after raking leaves together with some of the other sisters in Lower Hamlet in June 2019.

Q: Sister, you recently shared that you studied philosophy in Paris before becoming a monastic. How has your life changed and how did you end up raking leaves at Plum Village?

Sister Hien Nhan: Thank you very much for your interest. When I reflect on my life, I see that I’ve always been looking for something. Even when I was very young, I had this image of me going on a quest: a quest for truth, a quest for myself, a quest for the meaning of life. I’ve always had this sense that life was a quest. And I used to imagine many things about it when I was a child. For example, I thought that someone would come at night and take me out of bed, and we would go out to look for something together.

My ancestors—my parents and grandparents—have always been very talented in thinking and generally intelligent people. For example, my grandmother in Mexico has had her picture in many newspapers for being the first to do this study or that study. And my grandmother on my father’s side, even though she came from a very poor family, became a very good student.

So, I think that because of these conditions, I used my mind and intelligence to try to fulfill that quest. And then, quite naturally, this got me very interested in philosophy. In philosophy, there is this sense of looking for the truth, looking for what we really are, looking for what it means to be a human, and looking for how we can live our life fully.

I studied wholeheartedly and I really loved philosophy with my heart, as well as my mind. And philosophy was really a quest with my whole being, not only an intellectual thing. But when I studied in Paris, I realized that I got into an inner conflict that was really difficult because I recognized that the way the teachers at my school taught philosophy did not correspond with my own quest. And that it was a lot about studying and writing and staying in the intellectual realm of things. This included proving things through theory, but never trying to embody what we were writing, what we were debating about, and what we were reading.

It was a very difficult time because all my ideals about school, about my teachers, about philosophy, and about what I could achieve by giving myself wholeheartedly to this system kind of collapsed. And I already had some doubts in it before, too. For example, I remember when I was around seventeen, I tried some psychedelic experiences in hopes of extending my understanding beyond the intellectual world and seeing what’s behind it. It was also around this time that I got to know Buddhism and meditation. I realized that intellect was only the superficial part of our mind and our being, and that I had an interest in exploring deeper.

So, that’s how I went through psychedelic experiences and got in touch with meditation. But then, I realized later on—thanks to meditation, friends, and the support I received from practitioners—that actually this psychedelic experience was also a form of running away from my suffering. My whole life, I had always taken refuge in the intellectual world. I had learned not to look at my emotions that came from the difficult situations in my family and many other things. So, various conditions came together for me to realize that what I needed was not intellectual studies, but rather a concrete practice in my daily life that can really bring about a change in my whole being and not only keep me grounded in the thinking realm.

Raking leaves helps me to balance myself after so many intellectual years.

So, that’s basically my life’s journey. When I first came to Plum Village four years ago, it was really like a work of humility. In all the things I had been so good at, like the intellectual thinking and all of these things, I had been used to looking at myself as someone who knows, someone who is good, and someone who can do things, because I had always received this feedback based on my intellectual capacities. When I came here, everything that I didn’t know how to do, in a sense, is what was valued at Plum Village. So, suddenly I lost this image I had of myself and I had to learn to be the person who doesn’t know how to do this, who cannot do that, is not good at this, et cetera.

I remember the first time I cooked with the sisters. Here we’re around five sisters in the cooking team, and we cook for a hundred to three or four hundred people. I thought I could never do it and if one day I did it, then afterwards I would need three Lazy Days just to sleep. [laughs] And I remember the first day I was actually able to be in the kitchen the whole day and participate in that, I was so happy and excited I didn’t sleep even one minute the night before and the night after! And it stayed like that the first three days I cooked with the sisters: every time I was so excited that I didn’t sleep afterwards. [laughs]

Especially the first three years of living at Plum Village, it was so wonderful to see how many things I could learn. There just hadn’t been conditions for me to learn them yet. And then, I started to understand more and more. Actually, I was always very inspired by Thay’s teaching when he says that, “What we know we should be able to practice.” Or beautiful sentences like, “Cleaning the bathroom can be an experience as deep and as wonderful as sitting meditation.” Things like that. So, I had always been inspired by these statements, but I couldn’t really put them into action. But slowly, slowly I learned to go in this direction more and more. And I see that raking leaves and doing physical work is actually what I need to balance myself after so many intellectual years.

Q: Where do you see yourself after you finish the five-year monastic program?

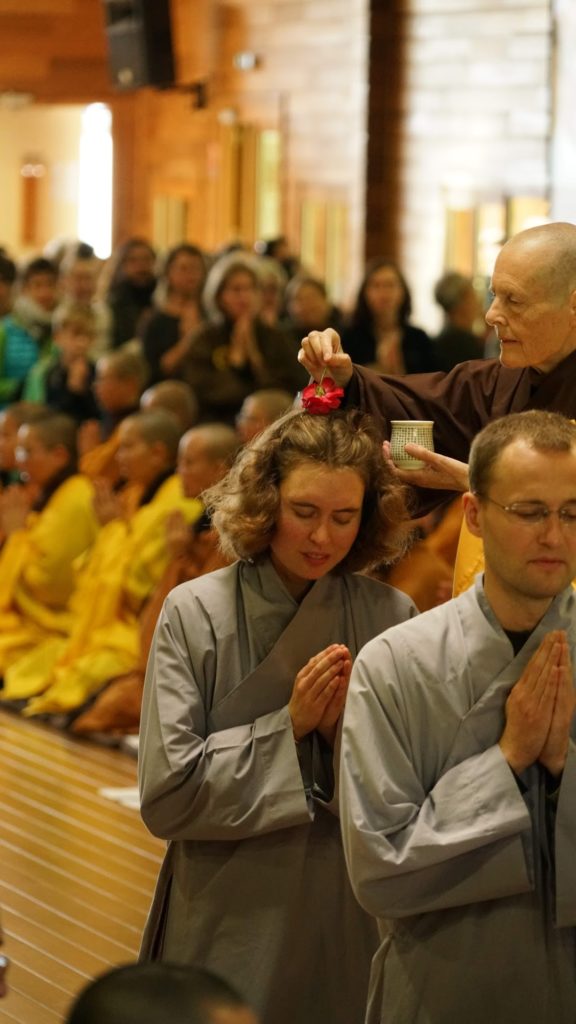

Sister Hien Nhan: I’m very grateful for this five-years program because I saw a fear of commitment to the monastic path for life. And I think that in our culture, especially for young people, there is this fear of committing to anything for life. So, I think that Thay could also see this and that’s one of the reasons why he opened this program. But actually, the truth is that since I ordained, there’s really a new source of joy and of clarity, and I’ve never felt as close to myself. So, more and more in my mind, I can imagine continuing for more than five years as a monastic.

I just see that living in community with the sisters is so beautiful. It gives us all the conditions that we need to transform, to look at ourselves. And with the Sangha, we can really fulfill all our ideals in terms of commitment and engaging with the world. The tools are all there. And we also have all the time needed to take care of ourselves and to let these ideals unfold. Because I feel when we’re out in the world, if we have many ideas to change, sometimes we don’t have the time and the conditions for our aspirations to mature and actually manifest at the right time. So, we feel this aspiration, but we go for them too young. And after that, we do not have the time to really mature ourselves. So, it’s easy to go into a burn-out phase or not to do it skillfully or to do it alone. But here, the Sangha has all of these ideals. So, if we’re not ready yet, the elders in the Sangha will do it for us. And then when we’re mature, we will take it on. So here, there’s really the time and the space we need.

The greatest gift […] is the presence of the Vietnamese community.

The last thing I want to say is that one of the greatest jewels and the greatest discovery I’ve experienced since ordaining is really that we as Westerners can learn everything from the Vietnamese culture. I think I understand more and more how Thay and the practice are really rooted in the Vietnamese culture even though we benefit from them so much as Westerners. I see that the values of harmony, of joy, of togetherness, of humility, and of kindness are all things that are there in the culture of Vietnam. I feel that this is the main condition that opens my heart and brings me back to all these values after so much societal conditioning and education that worries so much about individualism and intellect. So, I think the greatest gift I have received as a monastic is the presence of the Vietnamese community.

Interviewed by Annica Bauer on 25 June 2019. Transcribed by Diane F. Wyzga and edited by Erica Fugger.