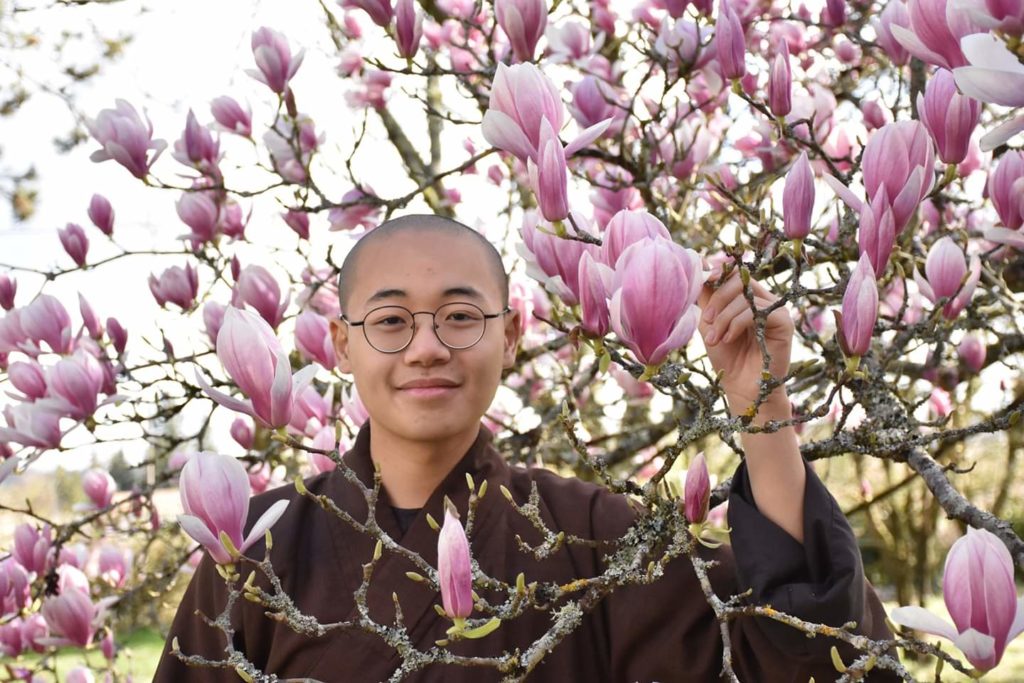

By Br. Chon Tang

I’m from Alberta, Canada, and I’m 19 years old. My father is from Northwest Vietnam, and my mother is from Central Vietnam. I came into contact with a Sangha at a young age thanks to my grandparents’ visits to the monastery. At that time, my grandmother still babysat me.

I enjoyed being around the monks, especially following my teacher everywhere he went. One day, I asked my mother for permission to become a monk, and she was very happy. She told me that when she was a young lady, she met two monks who were studying at a prestigious Buddhist university in Vietnam. They were blood brothers, and their mother had the same name as my mother’s.

This family inspired her so much that she hoped one day if she ever had children, they would become monks. This hope was instilled in my mother as her deepest wish. However, for my father, it was a different story. He couldn’t see any logic in my decision and didn’t support my monastic aspiration. In the end, without my father’s permission, I became a monk at the age of three. After I joined the monastery, he became upset and did not talk to me for a long time.

When I saw my dad again, I was about five or six years old. My father was happy to see me again after a long period of time and was moved because he missed me a lot. However, he didn’t want to visit the monastery. I learned a lot of new things, and I became more mature and calmer than boys at my age. Since my father could see this, he slowly got used to it and finally accepted for the continuation of my monastic journey.

My Monastic Volition

I didn’t have a very clear monastic aspiration at the age of three. The best way to explain my aspiration for becoming a monk would be thanks to my volition. For example, when a three-year-old child sees something they want, they may beg for it until you give it to them. If they don’t get it, they’ll keep bothering you until you give in. They might even cry or throw a fit.

Now that I am older and have stayed on the monastic path, my mother disclosed to me her special story about why she was so supportive of my decision on becoming a monk. When my mother was 29, she and my father decided to have children, but she went through two miscarriages.

Although they suffered great loss, my parents didn’t lose hope. They tried again for the third time. Unfortunately, five weeks into the pregnancy and for 18 consecutive days, my mother went through a lot of pain due to complications; she was in a dangerous state of life and death. In her deepest moments of suffering, my mother came back to the practice and invoked the name of Avalokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of great compassion to bring her comfort.

She remembered the aspiration she once had and hoped that I would safely enter into this world. At the end of August that year, there were still signs of pregnancy. Ten months later, I was born. To my mother, my younger brother and I have always been her biggest source of hope.

My mother also told me that when I started to talk and was able to choose my own food, I asked her if the food she made contained any animals. If any food contained animal products, I refused to eat it. When I grew older and playful, I was attracted to Dharma-related topics. For example, as a hobby, I collected many Buddha statues that I offered to others or looked through Dharma books I didn’t know how to read to find nice Buddha pictures. I played make-believe games and set up all of my teddy tears before my little shrine in a corner of my house and pretended to give them Dharma talks and personal consultations.

Although I had already entered the monastery, my teacher was very understanding. He allowed me to spend home visits with my family that often lasted two or three weeks. I spent a lot of time with my mother and father, and this is why my mother has so many memories of me as a young boy.

Besides my mother’s personal story, I think my motivation to become a monk at that age was mainly based on the fact that I looked up to the monks. In me, I had a deep volition to become a monastic. I just enjoyed the Sangha community, the connection between me and my teacher, and the feeling of comfort and interest I felt by listening to the Buddha’s teachings.

The Connection of My Root Teacher with Plum Village

My root teacher, who gave my first monastic ordination, is not related to Plum Village or Thay. However, he taught Thay’s teachings a lot. I remember when I learned the traditional verses—the gathas—for the very first time in Sino-Vietnamese. Later, my teacher suggested learning Thay’s revised versions of the gathas.

My teacher held Thay’s teachings and practices very close to his heart. Even the first chanting book we studied in English from my root teacher was the Plum Village Chanting and Recitation Book. My current teacher, however, studied under Thay as his student and was ordained as a Bhikshu in the Plum Village tradition. My older brothers in the Dharma were ordained in the same tradition as well and studied Thay’s teachings.

How Young People Can Bring the Mindfulness Practice Into Their Daily Lives

As a young monastic, I ponder a lot about how I can direct my efforts towards continuing the Buddha and Thay on the path, helping everyone benefit from the Buddha’s teachings, and helping them to enjoy living a mindful lifestyle. I always hope that in the future, we will be able to use mindfulness and the Buddha’s teachings in the most practical way in our daily lives to help each other become happier and live more meaningfully.

It is important that in everything that we do, we never forget that we are the continuation of the Buddha and Thay. They lived the Dharma and walked the path of awakening. By doing so, they brought countless amounts of joy, happiness to themselves and others. Seeing their success is a source of motivation for us to continue their path. If we practice, we can benefit ourselves and those around us.

Continuing their path can be as simple as holding the door for someone at school, taking care of yourself by meditating for 10 minutes a day, making a little effort to learn the dharma, offering someone your beautiful smile at work, or lending an ear to anyone who is going through difficulties. We have the capacity to practice, whether we do it full time or every chance we can, in our spare time to make the practice a part of our lives.

To my brothers and sisters, I hope we will continue to walk on this path of awakening like Thay and the Buddha themselves were able to do. Although many of us live all over the world, I think it doesn’t matter, because we can be one when we practice together. Together, we can wake up as a community.

Interviewed by Annica on May 9, 2019 and transcribed by Elaine Fisher.